Sumatra has always been more than an island.

It is one of the oldest pieces of land in the Indonesian archipelago — a place where forests once stretched endlessly, rivers carved their way through volcanic ridges, and trade routes connected distant worlds long before the idea of a nation existed.

At its southern end lies Lampung, a province that has served for centuries as a crossing point between worlds. It faces the narrow waters of the Sunda Strait, where ships have passed for hundreds of years, linking the Indian Ocean with the Java Sea. Through this strait came not only goods — pepper, resin, tin, coffee — but also ideas, languages, and beliefs. The people of Lampung became shaped by this constant movement. They learned early that the sea is not a border, but a continuation of the land.

Historically, Lampung was known for its pepper. As early as the 15th century, traders from China, India, and Arabia came to exchange textiles, ceramics, and metalwork for the sharp, dry spice that grew in the humid hills. For a long time, pepper was the economic lifeline of the region. Even during Dutch colonial times, Lampung remained one of the key export areas. Yet, as elsewhere in Sumatra, prosperity came with pressure. The forests that once sheltered wildlife and protected the soil began to shrink. The plantations expanded, and with them came new roads, migration, and dependency.

By the late 20th century, the transformation of Sumatra had become one of the fastest in Southeast Asia. Logging, agriculture, and urban growth changed the face of the land in only a few decades. In Lampung, large tracts of rainforest disappeared, replaced by coffee, oil palm, and cassava fields. What was once a natural buffer for rivers and wildlife became a managed landscape — efficient but fragile. Floods became more frequent; the soil lost its depth. The people adapted as they always had, but the balance between man and nature — once instinctive — grew uncertain.

Yet Lampung still carries something of the old world. In the northern parts of the province, near Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, the forest remains. Here live the last Sumatran elephants and tigers, moving quietly through the remaining corridors of green. Their presence is more than symbolic; it reminds the people of what has been lost and what still can be protected. Local communities and small cooperatives are learning again to work with nature rather than against it — planting mixed crops, protecting watersheds, and rethinking how farming fits into the larger environment.

The landscape itself holds traces of memory. Villages still follow the rhythm of the monsoon. Along the coast, fishermen repair wooden boats by hand, as their fathers did. Inland, traditional Lampung houses stand raised on stilts, a practical response to floods and insects, but also a reflection of social order — the space between earth and roof symbolizing harmony between human life and the world above. Though modern life presses in — with its asphalt, plastic, and electricity — these quiet patterns endure.

Lampung has always been a place of adaptation. Its people have faced volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and the long reach of economic systems far beyond their control. The 1883 eruption of Krakatau, just across the strait, destroyed entire coastal villages and changed the global climate for years. Yet within a generation, people returned and rebuilt. They did not speak of resilience then; they simply continued. This quiet persistence is perhaps the real heritage of Sumatra’s southern edge.

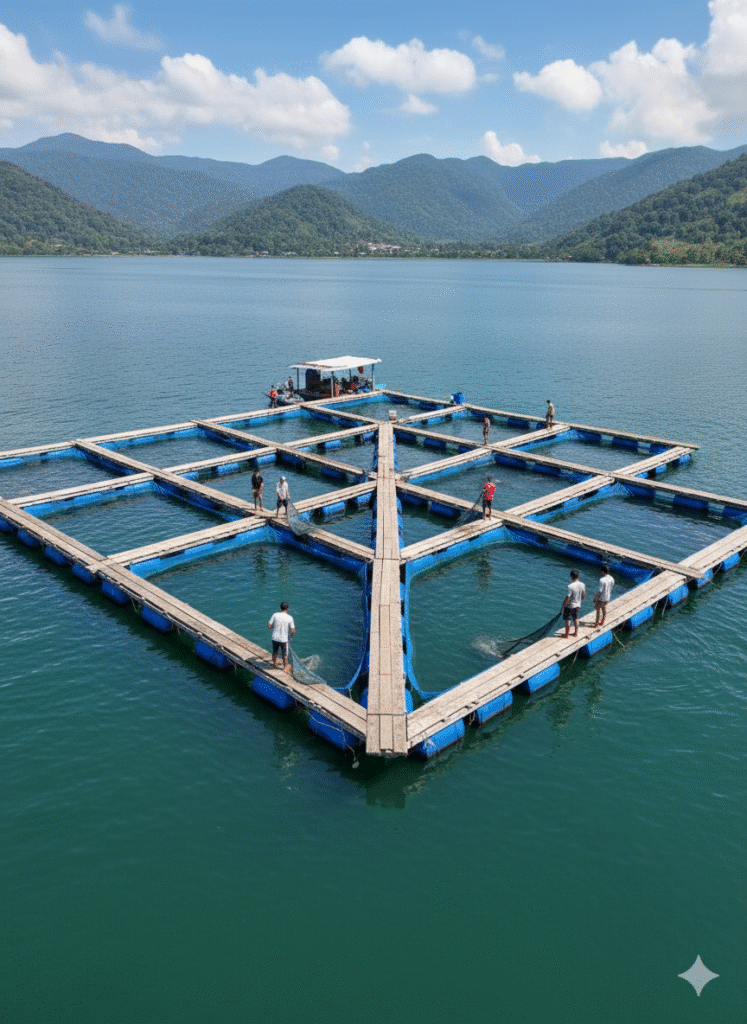

Today, Lampung stands between two realities. It is part of a modern Indonesia that seeks growth, connection, and progress, but it also stands as a reminder of the limits of extraction. The forests cannot endlessly feed the mills. The soil cannot renew itself without rest. And the sea, which has given food and trade for centuries, is now strained by overfishing and waste. The challenge is not to reject development, but to remember proportion — to rediscover the older knowledge that once guided how to live with the land.

In some areas, that balance is returning. Small farmers’ cooperatives in Lampung are experimenting with sustainable pepper and coffee production. Conservation groups are restoring mangroves along the coast, understanding that these quiet trees protect more than just the shoreline — they hold together the relationship between land and sea. The old idea that prosperity depends on harmony, not dominance, is finding new life in practice. It is slow work, but so was everything that once endured here.

Sumatra’s strength has never been in its monuments or its cities, but in its capacity to recover. The island is restless, shaped by earthquakes and the movement of tectonic plates, yet it endures because it bends rather than breaks. Lampung, at its southern tip, reflects that same principle. It is where the currents of nature and culture meet — sometimes in conflict, often in renewal.

Visitors who come here expecting untouched wilderness may be surprised. What they find instead is something more complex: a landscape where the natural and the human are already intertwined, and where survival depends not on nostalgia but on understanding the present. Lampung is not a museum of the past; it is a living example of what happens when tradition and necessity meet halfway.

Perhaps that is the quiet lesson of Sumatra’s southern edge. The world changes — sometimes violently, sometimes without notice — but the ability to listen remains. In Lampung, listening has always been more important than speaking: listening to the wind over the fields, to the sound of rain returning after months of heat, to the advice of elders who measure time by the harvest, not the calendar. It is in these ordinary acts of attention that balance can still be found.

To write about Sumatra and Lampung is to write about continuity — not the kind that resists change, but the kind that absorbs it. The island’s story is not one of purity or isolation; it is one of exchange, adjustment, and resilience. Its future, like its past, will depend on whether people remember that everything here — from the mountain to the mangrove — is connected by the same rhythm of survival.

That understanding is not romantic; it is practical. It has kept life possible on this restless island for thousands of years.

Published by Lobxr Editorial Team — inspired by Indonesia’s living connection between land, sea, and community.